Published in the Deseret News, April 7, 2017

By Allison Pond

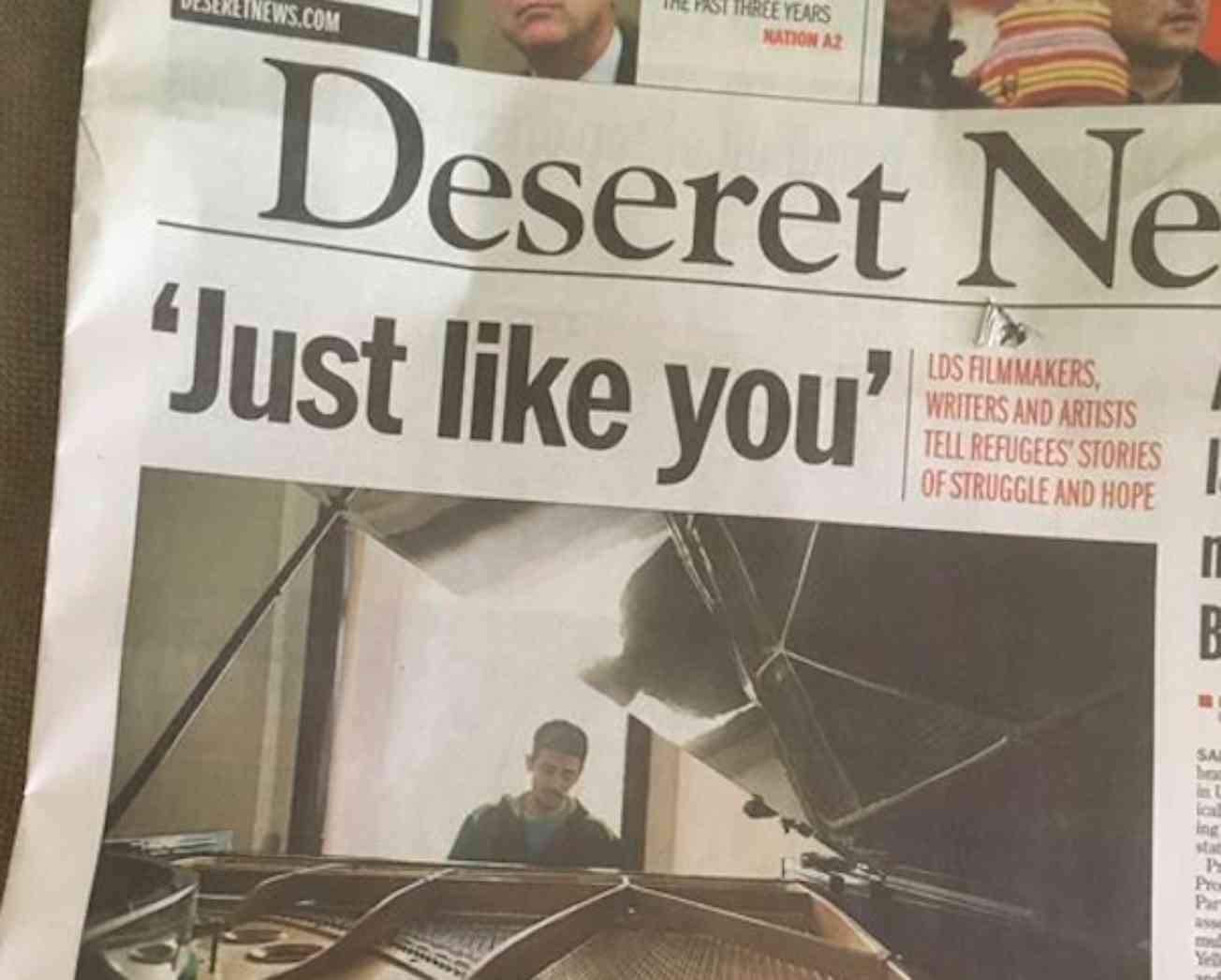

How these Mormon artists discovered that refugees are 'just like you'

Original article published on DeseretNews.com.

PROVO — Aeham was playing his piano on a street in Damascus when a sniper killed the young girl sitting by his side.

Ali helped carry several children nearly 3,000 miles from Afghanistan to Greece — walking on a prosthetic leg made from a broomstick and duct tape.

Roya was dragged by the Taliban to a public square in Kabul while she was pregnant with her third child and shot in both knees for the crime of informing women about vaccination and education.

Each of these refugees are now building new lives in new countries after harrowing journeys from their war-ravaged homelands. They are among the faces of the ongoing refugee crisis in Europe and the Middle East — faces with whom a non-profit group of artists and volunteers called Their Story is Our Story want you to become familiar.

“They want to be heard. Every single one of them … is crying out to all of us, saying, 'I'm human, just like you,'” said Trisha Leimer, president of TSOS, during a presentation to students at Brigham Young University on April 4.

TSOS is made up of artists and volunteers seeking to give voice to refugees and connect them with others through social media, art, photography, film, exhibits and publications. Most team members belong to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and became connected through social media.

Leimer and writer Melissa Dalton-Bradford were both Americans living in Germany in the same LDS ward when the influx of refugees started arriving in 2015. They volunteered teaching German and sewing to refugee women housed in Leimer’s daughter’s school gymnasium, and noticed that stories about the refugee crisis in the American press often didn’t match the accounts of the tender people they were working with on the ground.

Around the same time, in London, photographer Lindsay Silsby had a dream that she was in a refugee camp in Greece taking photos of refugees. She shared it with Seattle documentary filmmaker Garrett Gibbons, and through Facebook the two connected with Leimer, Dalton-Bradford and Utah artist Elizabeth Benson Thayer.

The group talked on Skype and their collaboration culminated in a July 2016 trip to the Oinofyta refugee camp in Greece, which was being managed by Lisa Campbell, another LDS woman. The team spent three 14-hour days interviewing, filming, photographing and sketching 48 camp residents who lined up to tell their stories.

“It wasn’t all that dissimilar from what I do in a normal shoot,” said Silsby, the photographer. “There were mothers loving on their children, husbands with their wives, grandparents and cousins and aunts and uncles. All that really separated these people from me or the people I'm used to photographing was their circumstances and the atrocities that lay behind them.”

Portrait artist Thayer said that in the absence of a shared language, she bonded with her subjects by looking in their eyes, drawing their features and sensing what was in their hearts. Children flocked to her, and at first she was annoyed when several men pushed the children aside and seated themselves for a portrait.

“But then I realized that they needed some sense of dignity and sense of self — to know that ‘I am still a person and I am still important,’” Thayer said. “That's when my heart changed, and I spent as many hours as I could drawing because I felt it was an affirming experience for them.”

The refugees

After the trip to Greece, the TSOS artists went on to Germany to profile refugees there. They’ve kept up with refugees they met in both places, in some cases assisting as the refugees find their way to new countries and begin to integrate.

One of them, Aeham Ahmad, is a classically trained concert pianist from Damascus. When his house was bombed, he wheeled his piano into the street on a vegetable cart and continued to play Western classical music — Bach, Beethoven — and other songs for people to sing along with.

After a young girl sitting next to him on his piano bench was killed by sniper fire and his piano torched by ISIS, he fled to Europe, one of hundreds of thousands of men who fled to prepare the way for their wives and children who would follow later.

Aeham has been reunited with his family in Germany, where he has made a name for himself as a performer and music teacher. But instead of Western music, he now feels drawn to play Syrian songs of lament and grief for his homeland. When he learned TSOS would be presenting his story to people in the U.S., Aeham asked them to pass along a message: “Please, will you help us? Will you let us in?”

Roya, who TSOS met in Greece, is also building a new life in Germany with her children. In Afghanistan, she had studied biology and physics against the wishes of the man she was married off to at age 15, and began educating other women on health issues. She was unable to leave her house for two years after being shot in the knees by the Taliban, but when she finally could, she set out on foot on a 3,000-mile trip to Greece with her daughters.

Like hundreds of thousands of refugees, Roya boarded an overcrowded rubber boat knowing she couldn’t swim and that many boats capsized before making it to Greece. Out of all the oppression and horrors refugees have experienced, the boat crossing is what refugee women like Roya cry about when they tell their stories, Dalton-Bradford said.

Many refugees strap their cell phones to their chests for the boat ride, Dalton-Bradford said, because other belongings can be thrown overboard by smugglers and phones are their one lifeline to family, to maps, to information about where to find shelter and support. Whenever they arrive in a new location, they search for wifi and power outlets to charge their phone batteries.

TSOS has also kept up with Ali, who made the same trek from Afghanistan to Greece on a prosthetic leg made from a broomstick. (Ali and names have been changed to protect their identities.) The volunteers helped find a donor to pay for a newer, more functional leg for Ali, but he left it behind in Greece when he set out for France because he feared smugglers would steal it.

Months later, Dalton-Bradford put out a Facebook request to friends in France to look for Ali, who had traveled there clinging to the undercarriage of a truck for 36 hours. One of her friends recognized Ali at a bus stop — an instance of what Dalton-Bradford calls the "divine choreography" that has characterized TSOS's work — and Dalton-Bradford arranged for a missionary to bring Ali’s new leg to her in Germany. She then personally delivered it to him in France, and says of that trip, “I’ve never been so happy in Paris.”

While many refugees are anxious to tell their stories, Dalton-Bradford said, others are often afraid.

“They have lived for years fearing their government, fearing warlords, fearing extremists, and if they tell their story it could mean that they are killed,” she said. “The idea of sharing your honest story is foreign to them. They know if they share their story it might endanger their family that's still left in a bombed out Aleppo or Damascus or Homs or Mosul or Kabul.”

So they let the refugees lead. “(We) say, we are here to listen, and you can tell us as much as you want,” Dalton-Bradford said.

“The majority of the time it's been this gushing, this outpouring of ‘Here's who I am’ and ‘You care and you want to know? You're an American and you want to know about me, an Afghan? That's not what my government was telling me you Americans were about.’ Their perception of who we are is as contorted as what Americans think they are,” she said.

Being a friend

In addition to giving money or volunteering in traditional ways, Dalton-Bradford said people can help refugees by connecting with them as friends, both in their own communities and on social media from across the world.

TSOS’s Facebook page and organizations such as We Are Like You connect people with refugees, many of whom are hungry to communicate.

“They become people that you know. You can humanize them in your own circle,” Dalton-Bradford said.

“How does that help them? It helps them because they are stuck,” Leimer said. “They are stuck because of fear. People don't have information about who they are, what they're really there for and why they can't go back.

“It disturbed me when I heard (people say) they are terrorists. Because these people that I know, they are not terrorists. In fact, they are victims. They have been so victimized by the very people we are accusing them of being.”

Refugees are deeply invested in making Germany safe, she said, because they don’t want it to fall to the same people who took over their home countries. They are uniquely able to help spot extremists and root them out, acting as an early warning system, she said.

“We are at a crossroads,” said Leimer. “There are more people displaced than ever before. … Even though there's an ocean separating us from them, the consequences are going to be paid by the entire planet. Your children, my children and my children's children are going to deal with what we decide to do or don't do today.”

Dalton-Bradford called on the students at the BYU presentation to join TSOS in sharing the stories of refugees.

“This is a human opportunity for us to live our faith, to live our real religion. Because when you strip everything down, this is what it's about. Will we cross that road and care for our brother, or will be build more walls and pretend we are not all part of one great human family?” she said.

“Every one of us (involved with TSOS) would say this has changed us, this has expanded us, this has blessed us. This has been a new beginning for all of us.”